BAckground

“The most charismatic animal on this planet, the tiger has inspired mankind for centuries. We must find a way to secure a future for the tiger on our planet, through concerted, unwavering effort, before it is too late”

Belinda Wright, Wildlife Protection Society of India

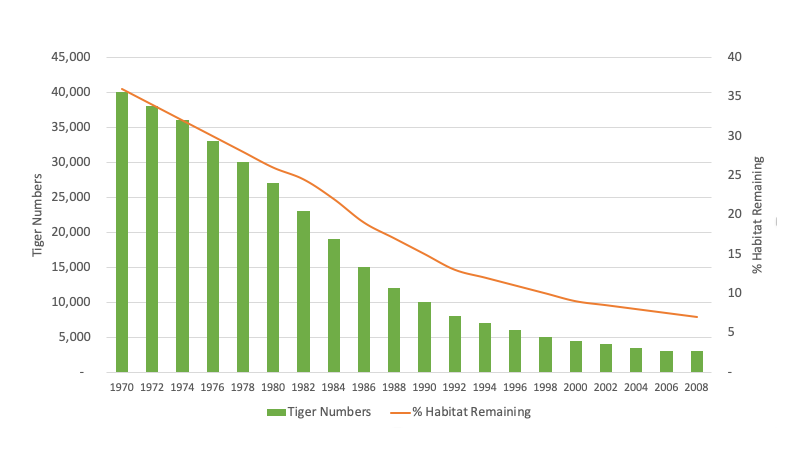

At one time, there were 300,000 tigers across India and SE Asia. By 1916, this had dropped to 100,000. Numbers fell dramatically, and by 2008, there were an estimated 3,500 tigers left in the wild. Numbers have recovered slightly to approximately 4,485 individuals (3,726-5,578) of which around 3,682 are in India. With pressures remaining, the survival of the wild tiger is hanging by a thread.

Tigers need forest cover, and may be found in tropical evergreen forests, deciduous forests, mangrove swamps and thorn forests. Tiger distribution and density in these habitats vary with prey availability, terrain and forest cover. They are also negatively impacted by human pressure: undisturbed habitat, effective protection from poaching and security of their prey base are paramount to their survival.

Tiger History

Over their evolutionary history, tigers (Panthera tigris) split into nine subspecies, all of which persisted until 1940. During the following four decades, however, three became extinct:

- Bali tiger – P.t.balica – extinct since 1940’s

- Caspian tiger – P.t. virgata – extinct since 1970’s

- Javan tiger – P.t. sondaica – extinct since 1980’s

Only six subspecies remain (global wild population estimates in brackets):

- Bengal Tiger – t. tigris (4,270)

- Siberian (Amur) Tiger – t. altaica (500)

- Sumatran Tiger – t. sumatrae (400)

- Indo-Chinese Tiger – t. corbetti (220)

- Malayan Tiger – t. jacksoni (150)

- South China Tiger – t. amoyensis (functionally extinct)

In the 19th Century, tigers were found throughout India. Even today, relic populations punctuate the map from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin, except in Punjab, Kutch and the deserts of Rajasthan. In the northeast, tiger range extends into Nepal and Burma.

Current Situation

Tiger numbers have been increasing over recent years but as young tigers reach ~18 months old they are forced to move on from their original habitat.

Tigers dispersing from the core areas of tiger reserves has led to an increase in conflict on the fringes of the park. The key to continued success lies in maintaining a positive attitude within the numerous villages affected by living alongside wildlife and the natural environment. Improving attitudes and awareness across a wide area is the focus of this proposal.

There are around 4,485 (3,726-5,578) tigers left in the wild, living in the forests in tropical and subtropical Asia, now only <6% of their historic range. They are classified as Endangered by the IUCN Red List and numbers, globally, are decreasing.

India supports an overwhelming majority of the global tiger population, harbouring ~3,682 Bengal tigers (Panthera tigris tigris), and numbers have increased by more than 65% since 2014 as a result of concerted conservation efforts by the Indian government and its partners over several decades.

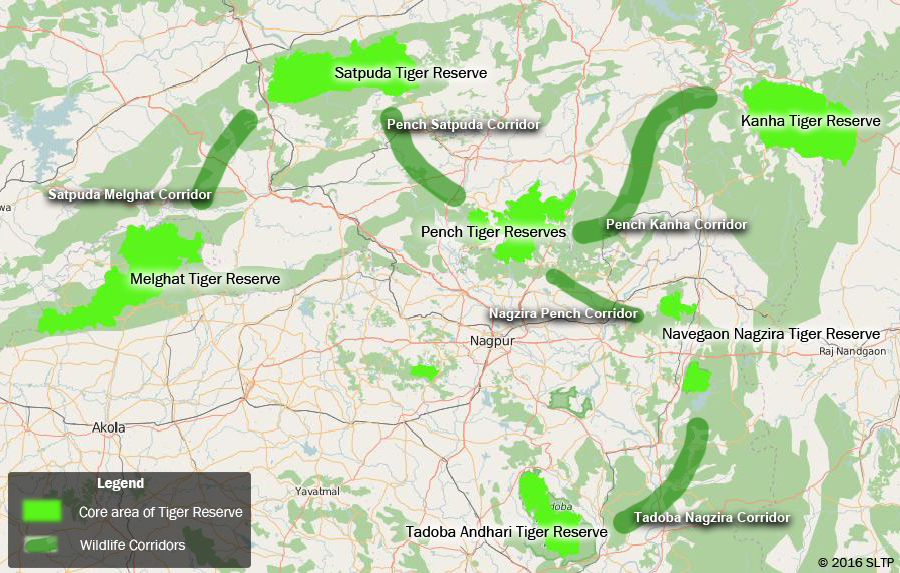

Central India

Central India supports around 1,100 of these tigers, which comprises several tiger reserves (Satpuda, Kanha, Melghat, Pench, Navegaon-Nagzira, Bor, Tadoba-Andhari, Bandhavgarh and Panna) falling within the officially recognised Central India Tiger Conservation Landscape cluster, and associated corridors that stretch across two states: Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. The Satpuda landscape is the largest viable block of tiger habitat in India; therefore, offering the best hope for India’s remaining wild tigers.

Tiger Populations

India harbours a significant proportion of the world’s tiger population in 18 of its States, largely due to good forest cover (678,000 km², or 21% of the country), and a network of over 950 Protected Areas with a wide coverage of habitats. These include 54 established Tiger Reserves.

The tiger’s survival depends on the protection of large landscape complexes, of which there are six in India:

| Potential tiger habitat (km²) | Estimated tiger population | |

| Central Indian Landscape | 47,122 | 1300+ |

| Western Ghats | 51,000 | 1080+ |

| Shivaliks & the Gangetic Plain | 20,800 | 815+ |

| Eastern Ghats | 15,000 | 120+ |

| North-East Hills & Brahamaputra Plains | 136,000 | 230+ |

| Sunderbans | 1,586 | 100+ |

Loss of tiger numbers and habitat

Whilst these forest landscapes encompass virtually all the viable tiger habitat remaining in India, and offer hope for the species’ revival, they are fragmented by human settlements, agriculture, mining, dams and roads. Unabated, indiscriminate development that fails to take into account potentially negative environmental impacts is driving the disappearance of these crucial forests and their tigers.

The single largest population of wild tigers in India is that of the Western Ghats landscape comprising Nagarhole, Madumalai, Bandipur and Waynad. The relative conservation success of the Western Ghats serves as a good example of inter-state management of Tiger Reserves securing a tiger meta-population with a good long-term prognosis and providing a resource with which to repopulate neighbouring forests.

Why Should We Protect Tiger Habitat?

The Bengal Tiger is an apex predator and an icon of strength and mystery. Its pure symbolic significance cannot be underestimated. If we can save the tiger we can save the planet – all it takes are committed people to make it happen. Success will breed success.

The Bengal Tiger subspecies is at the top of the food chain in the wild. But tigers are also a vital link in maintaining the rich diversity of nature. When tigers are protected, we save so much more. For example, with just one tiger, we protect around 25,000 acres of forest.

It’s not just the tigers that need protection. The forests they inhabit are essential watersheds: over 300 rivers and numerous streams originate from India’s six major tiger landscapes, providing water to millions of people downstream. Thus, for India’s long-term water security, protection of tiger habitat is of paramount importance.

Besides water catchments, these forests play a crucial role not only in carbon sequestration – of critical significance to mitigating climate change – but also safeguarding biodiversity. With recent advancements in medical science, there is a growing recognition of forests as gene banks, with a plethora of plants, fungi and animal species as potential sources for the treatment of human illness. Equally relevant, several million people across India depend on direct benefits and services from forests for their livelihood, including livestock grazing, fuel wood, forest products and building materials.

Poaching is, without doubt, the greatest threat to tigers in India, driven by the illegal trade in tiger skins and body parts to satisfy demand, particularly from China. Whilst the magnitude of the problem has been acknowledged by the authorities, lack of political will, poor enforcement and intelligence, inadequate trans-boundary co-operation and a strong criminal network controlling the trade in urban and cross-border areas continue to undermine the tiger’s survival.

Between 1994 and 2008, WPSI (Wildlife Protection Society of India) documented the poaching and seizure of 853 tigers. Over 1,400 people have been accused in connection with these cases, yet there are records of only 14 convictions having being brought. Most worryingly, these figures are incomplete and represent only a fraction of the actual poaching activity believed to have occurred in India during that period.

Yet wild tigers face a variety of other threats, such as poaching of their prey base, competition with livestock encroaching on their habitat, deforestation of land converted for agriculture, and direct conflict with rural communities competing for the same forest resources, often resulting in fatalities on both sides.

- Habitat loss and fragmentation

- Depletion of prey base

- Poaching for tiger parts

- Retaliatory killings

Since 1994, according to a WPSI database, poachers have killed an average of 56 tigers annually. These figures most probably represent only a small fraction of the real levels of tiger poaching in India.

The Tiger Crisis

Wild tiger numbers have fallen dramatically by >95% and have reached critical levels. Whilst the tiger could survive in zoo’s it is our aim to manage the crisis to ensure that wild tigers remain in the wild. There are some signs of a recovery from disaster – but we are not there yet and much remains to be done. Governments need to act, and NGO’s such as Saving India’s Tigers, can help guide policy and activity.

The future for wild tigers is precarious, bordering on disaster. In 1973 it was revealed, to the shock of the nation, that India’s tiger population had plummeted from an estimated 40,000 at the turn of the century, to less than 5,000. In response, Mrs Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India and avid conservationist, took immediate steps to protect the tiger and its habitat by launching Project Tiger. Despite some notable successes and a brief population recovery, without which the tiger may arguably already be extinct, Project Tiger struggled to halt their precipitous decline.

Today, we are immersed in a second tiger crisis. The Prime Minister of India is equally determined to save tigers, yet, despite committing resources and initiating various measures to protect the species, competing political issues often take priority. Against a backdrop of a burgeoning human population, desperate to overcome poverty, the threats to tigers are greater now than they ever have been.

The Satpuda Landscape

Our ambition is to see a green haven at the heart of India with growing tiger numbers and supported by local people. The Satpuda landscape is unique. It has inspired people from the author of Jungle Book, Rudyard Kipling, to visitors from all over the world. Saving this landscape is not just a challenge for India but a global challenge – it form part of our global heritage.

The Satpuda Landscape highlands of Central India – a mountain range that has captivated the imagination of millions and was the inspiration for Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book stories. Steep hillsides give rise to streams and rivers. Forested plateaux cradle fragile, nature-dependent communities. These forests are home to apex predators – tigers, leopards and Asian wild dogs – as well as prey species such as the spotted deer, sambar and the mighty gaur.

Amongst the last remaining dry deciduous forests across the globe, the Satpuda Landscape is one of India’s – and the world’s – most important tiger habitats. Here, forest corridors connect a patchwork of Tiger Reserves and protected areas, whose health and integrity are crucial for the survival of the magnificent striped cat and other wildlife.

The dramatic decline of the tiger in India has reinforced the urgent need to keep this landscape, an estimated 25,000 km² of contiguous forest corridors, free from harm.

These forests are rich in biodiversity and also key to the water security of millions of Indians. A myriad of seasonal and perennial rivers originate in the Satpudas, delivering essential ecosystem services to the surrounding human communities.

As in the rest of wild India, the problems facing wildlife in the Satpudas are numerous and complex. And if the tiger vanishes from the Satpuda range, the reduced incentive for protection would, almost inevitably, consign the forests to the same grim fate.

Tiger Reserves of the Satpuda landscape

We are working in 10 parks in the Satpuda Landscape – these parks consist of core protected areas, buffer areas adjacent to the parks and corridors that connect the parks genetically. Just in our area we have >500 villages and >3 million people in the Buffer Areas.

The Satpuda landscape is a Tiger Conservation Unit (TCU) and considered by the Indian government as a Priority-1 tiger conservation area. Protected areas total over 7,000 km², which include about 2,000 km² of tiger habitat that is devoid of human presence.

The core areas are protected by government legislation and villages are being slowly relocated from these areas. The areas average 600 sq km each and it is considered that nearer to 1,000 sq km is required to house a stable wild tiger population; therefore additional areas are urgently required.

The buffer areas contain >500 villages and >3 million people living in the Satpuda Landscape. Just in the immediate area within 1 km of Bandavgarh core area there are 50,000 people living. It is crucial to develop a model where wildlife and people can co-exist and our work is very much oriented towards this goal.

The parks are tenuously connected by corridors – loosely defined forests through which wildlife can travel. These corridors are essential for the genetic health of tigers to ensure good x-breeding between populations. It is proving increasingly hard to protect these corridors from development and there remain numerous threats to the longevity of these corridors.

The States of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra in Central India have staggering rural population densities in excess of 150 people per km². With most of India’s tigers living in small, more or less isolated populations, it is no surprise that they increasingly range outside Tiger Reserves into buffer areas and corridors that are not afforded significant protection. Consequently, they regularly come into direct conflict with surrounding farming communities and livestock, with negative impacts for tigers and people.

Risks

Whilst these forest landscapes encompass virtually all the viable tiger habitat remaining in India, and offer hope for the species’ revival, they are fragmented by human settlements, agriculture, mining, dams, railways and roads. Unabated, indiscriminate development that fails to take into account potentially negative environmental impacts is driving the disappearance of these crucial forests and their tigers.

Whilst poaching has grabbed the headlines and remains a major risk there are other risks that need active management. Our programmes are tailored to mitigate these primary risks:

Click below for more information.

Habitat loss and fragmentation

Less than a hundred years ago, tigers prowled all across the Indian subcontinent. Exploding human populations, particularly since the 1940s, have resulted in major loss of tiger habitat. Habitats are further fragmented because of agriculture and the clearing of forests for developments like road networks. This forces tigers into small and scattered habitat patches.

Linear infrastructure projects

Whilst the need for industry and wealth creation is recognised some of these developments come with a considerable environmental price. The construction of linear infrastructure such as roads, canals, train tracks, power lines etc has the effect of breaking up the natural habitat and creating a mortal hazard for wildlife as it tries to cross these new features in their landscape.

When the need is such that the project must go ahead the incorporation of certain mitigation measures such as underpasses can help alleviate some of the problems created – it’s a fine balancing act.

Mining

As for linear infrastructure projects the need to create employment and wealth needs to be balanced with the needs of the natural environment and this is the case also with mining.

Many mining operations come with the need to build connecting roads along which travel lorries and other vehicles servicing the mines and removing the mining product which severely disturbs wildlife and habitat in the area. The additional roads provide access for illegal removal of forest wood and for poaching. The mines themselves can often desecrate large areas of natural forest.

Sometimes the legal protection afforded to certain forests are altered to allow mining in the area. With the emergence of eco-tourism local villages now help in arguing the case for a balanced approach.

Depletion of prey base

Tigers suffer from a severe loss of natural prey like deer and antelopes. Prey numbers decline because of direct poaching for meat and trade, competition with livestock over food and habitat degradation because of excessive wood removal for fires.

Poaching for tiger parts

Before the international ban on tiger trade in 1993, tiger populations were being decimated by poaching and trade. Despite the ban in the past few decades, the illegal demand for tigers as status symbols, decorative items, and folk cures has increased dramatically, leading to a new poaching crisis. Poaching driven by the international illegal wildlife trade is the largest immediate threat to the remaining tiger population.

Retaliatory killing

As tigers continue to lose their habitat and prey species, they are increasingly coming into conflict with humans as they attack domestic animals—and sometimes people. In retaliation, tigers are often killed by angry villagers.

Throughout the entire Satpuda landscape, grazing has become one of the most serious threats to tigers. In Melghat alone, over 125,000 cattle graze each day inside and around the fringes of the reserve. Forest fires, illegal logging, and the collection of fire wood and non-timber forest products (NTFP) all add to the existing pressure. In addition, indigenous peoples residing in the Satpuda range are also known to hunt wildlife – usually the same species on which tigers prey – for meat.

These pressures result not only in the degradation of habitat, but also in a sharp increase in human-wildlife conflict. In Tadoba-Andhari and its peripheral forests, 53 people have been killed by tigers in the last four years alone.

Commercial logging further deteriorates the forests and leads to monocultures that can support minimal biodiversity. With India on a fast-track to become an economic Superpower, the recent surge in large, environmentally insensitive development projects poses a real threat to the Satpuda landscape and its tiger inhabitants.

Corridors and Buffer Zones

Tiger reserves are unique to India and target federal support to an assemblage of tiger habitat including national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and protected forests. They include central core areas, classed as ‘inviolate’ and in which no resource use is allowed (i.e., no cattle grazing or gathering of non-timber forest products, etc.) and buffer zones.

Tiger reserves are interconnected either directly or indirectly via a network of corridors. These corridors encompass areas of non-protected forests and agricultural land, that are settled and often heavily used by people. Corridors are crucial to tigers to allow expanding populations to disperse and move between reserves, maintaining genetic diversity of otherwise isolated tiger populations. Tigers require vast areas of suitable habitat free from intense human pressures, to access a sufficient prey base of large ungulates (e.g., wild pigs and deer), and to defend their territories of 20-400km2.

Continuing decline in area, extent and quality of habitat, because of increasing human population, land-use change, pressures inside around and between tiger reserves, etc. when combined with increasing tiger dispersal from the core areas from the tiger reserves into buffer zones and corridors leads to increasing competition for land and resources with local people and resulting conflict. This may be the greatest threat to tigers across the landscape. Human–wildlife conflict involving tigers manifests as carnivore attacks on livestock and people, and retaliatory killing of carnivores by people.

Living with Tigers

Most rural families keep livestock, which are put out to graze daily. Between 400 and 500 cattle are killed annually by leopards and tigers in Kanha Tiger Reserve, for example, with over half attributed to tigers. Losing livestock to tigers can incite anger or frustration, with farmers retaliating either by shooting or poisoning.

Gathering of non-timber forest products (e.g., Mahua fruit used to make a local liquor) is done from dawn to dusk, putting people at risk of encounters with wild animals. Families are eligible to a government pay-out scheme should someone be harmed or killed by a carnivore; however, compensation is difficult and slow to access; in the meantime, anger and fear may lead people to retaliate by killing wildlife. This chain reaction is of particular importance in the heavily human-dominated corridors between tiger reserves, with tigers often unable to use and move safely through them, thus dramatically impacting upon their successful dispersion and breeding.